Build Date: Sun Dec 28 06:50:14 2025 UTC

My fits of Joy are soiled by relentless flashbacks and ghosts too foul to name

-- HST

| Interview with Seth Shostak —Reported 2001-12-21 19:42 by Siduri | |||||||

|

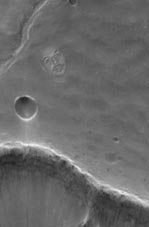

The Face on Mars "The aliens aren't contacting us because we're so bad."

TCS: Well, what about alien visitation thousands or millions of years ago? What about faces and pyramids? Seth: You mean on Mars? TCS: On Mars. Seth: Well, they look like faces, until you take high-resolution photos, and then they look like mountains. And mountains on Mars are not quite as remarkable. I have to admit that certain individuals have gotten a fairly decent living out of this idea. I can't begrudge them that too much. But really, have you seen the high-resolution photos of the face on Mars? TCS: Yes, I have. Seth: And what did they look like to you? A face? TCS: It looked like a bunch of rocks. Seth: Doesn't it? Maybe that's what it is. I know it is radical. TCS: I have associates who would swear that with the high-resolution photos it looked more like a face. I didn't see it. Seth: I don't see it either. People send me pictures of clouds and they say, "Look what's in this cloud! It's a picture of a guy sitting on a horse. This is clearly alien activity." People do that. And indeed, if you sit around and look at clouds you will see things. But it's a big step to say that it's alien activity. I have to say, when the local paper, the Mercury News, called me up the night before the Mars Global Surveyor was going to take its first high-resolution photos of the face on Mars, they said "Well Seth, what do you think they're gonna find?" "Well, I don't think they're going to find bulldozers all around or whatever. I think that this is akin to going to Safeway and buying a ten-pound bag of potatoes and looking at those potatoes. And you'll see faces in there, but it would never occur to you that this is an attempt by the spuds to get in touch." And she ran it just like that too, by the way. Mark: So you see faces in things. Do you think that's something that humans are hardwired to do?

You know, they do experiments. In Scientific American they did this years ago, where they take a picture of Lincoln or something. Everybody knows this guy. And what they did is they just pixellated it, they just reduced it to, like, 16 pixels or 25 pixels or something, some small number of pixels. They made a 128 pixel version and a 64 pixel version, and they would show this to people and they'd say, "Can you tell who that is?" "Oh, it's Lincoln." Okay. Then they'd give them the low-resolution version, see how many could tell that was still Lincoln. And it turns out you could tell it was Lincoln even when the number of pixels was really small; I don't remember the number. Which means that your brain is really good at recognizing faces. So the fact that you faces on the rocks on Mars, that doesn't surprise me. If anybody saw vacuum cleaners on the rocks on Mars, that would surprise me. Because you're not so good at that. But they don't, they find faces. They find the one thing that we're really good at finding. Siduri: Do you think SETI is a service to society? Seth: Is it a service? No, I don't think of it as a service, but I think that it's something that's very human. In the sense that one of the few things that distinguishes us perhaps from other animals, to some extent, is curiosity. We certainly are driven a lot by curiosity. And there are plenty of animals that have a certain amount of curiosity, because curiosity has survival value. But we turn curiosity to our advantage. When we learn something, we take advantage of that knowledge, because we can pass knowledge on. It's like any other basic research. It's knowledge for its own sake, and for the curiosity of wanting to know. Why does anybody want to know how the maria on the moon got formed? Who cares? But the fact is that people are interested, and in the end, that knowledge in the aggregate always pays off. In that sense it will be a service, if you found something. Either you would be in touch with a very advanced civilization, which is one possibility, or you don't understand anything but at least you know that there are others out there, and that gives you perspective. Sort of like the Copernican revolution. What do you care whether the Earth goes around the sun or the other way round? Didn't make much difference in the prediction of the planets in the night sky, actually. So it didn't have much practical benefit right away. But it turned out to be a service, if you will, to humanity to know. Mark: If an advanced alien society were to come in contact with us, would you be embarrassed about humanity in its current state? Seth: No. No, no, no, no. That's sort of a provincial point of view, that the aliens aren't contacting us because we're so bad. Why didn't they contact us back in the year 1100—we weren't destroying the environment then? "Well, we were bad, because we were conducting the Crusades." Okay, okay. How about back in the time of Julius Caesar—nobody was destroying the environment then; there weren't enough people to have any effect on the environment. "Yeah, but they were at war with the Phoenicians, those bad guys." We're always doing bad stuff. So to say now it's the environment, well, I mean, there's plenty to worry about as far at the environment, but I don't think they'd be too worried about what we do with our earth. Remember Michael Rennie? [general noises of dissent] Seth: The Day the Earth Stood Still? Well, you're all too young to remember him. It was a film, back in... TCS: "Michael Rennie was there the day the earth stood still, and he told us where we stand." That's right. Seth: Yeah, yeah, yeah, exactly. He stands there up at the end and says [in tinny voice] "What you people do with your own planet is of no concern to us. But when you threaten the galactic..." Whatever. And you get these big robots coming down and they're like mom, they're going to take you in hand. No, I don't think they care so much what we do. It's like, why do we care? I don't care what the ants do in their own anthills. They're probably wrecking things down there but it just doesn't really phase me much. So I wouldn't be embarrassed. |

|||||||

At this point the tape ran out. But for the record, Seth Shostak denies ever smoking up with Carl Sagan.

T O P S T O R I E S

The Crossroads are real and The Blues is a place; The enduring myth of Robert Johnson (More...)

California Glory Hole attracts huge crowds

A glory hole at Napa's Lake Berryessa is drawing huge crowds. According to Chris Lee, the general manager for the Solano County Water Agency, the glory hole hasn't been active since 2019, and only restarted operations on Feb 4. (More...)

Republican State Senator busted after soliciting a teenage girl

Republican State Senator Justin Eichorn of Minnesota was arrested for soliciting a teen girl on Monday just hours after he introduced a bill proposing "Trump derangement syndrome" (TDS) as a form of mental illness. (More...)

Parents claim measles is not that bad after having only one child die

The parents of a Texas girl who died from the measles are defending their decision not to vaccinate their daughter. "She says they would still say 'Don't do the shots,'" an unidentified translator for the parents said. "They think it’s not as bad as the media is making it out to be." (More...)

Delusional rich man tries to fire town staff

"I'm mayor now" said write-in mayoral candidate and founder of Pirate’s Booty Snacks Robert Ehrlich after losing the election for Mayor of Sea Cliff, NY. Then he tried to take over the Village Hall and fire everyone. (More...)

Musk claims Xitter security is staffed by idiots

Earlier this month Xitter experienced a massive outage. In an interview, Musk told Fox Business that he believes the attack came from "IP addresses originating in the Ukraine area." (More...)

C L A S S I C P I G D O G

The quest for knowledge never ends at the super top secret Spock Mountain Laboratory, although it is frequently interrupted by beverage breaks. Recently, a team of crack ethnomixologists returned from a dangerous expedition to the frozen expanse of Canada with the much sought recipe for a Spocktail that is destined to replace blunt force head trauma as the major cause of brain damage in the civilized world. (More...)

Paranoid Strippers & Psychotic Crack Dealers (Tales of Christmas Eve)

Christmas day, for the last 17 or so years has bored me. I find that the real fun and excitement always takes place on Christmas Eve. Every other year, it's the excitement of the metaphorical hunt instead of the kill. Otherwise, it's just plain bad craziness. (More...)

The Deep Dark Underbelly of the Star Wars Myth, or Ramayana Remembered

It's a fact: Star Wars is a blatant plagiarism of an ancient Asian legend, and the long lines of devout Star Wars freaks are really unscrupulous Asian copyright busters. From Indonesia to Thailand to Nepal, videos are available for sale or rent before they're even released in the US and UK due to this nerdy camcorder-clutching bunch. (More...)

Spock Went, Spock Wrote, Spock Kicked Ass

Every Labor Day weekend a large portion of the PDJ staff joins 30,000 other freaks at one of the biggest and strangest art festivals in the world - Burning Man - somewhere on the edge of the Black Rock Desert. Our base of operations is always the ultra swank Spock Mountain Research Labs - the World Leaders in Beverage Science and Leisure Technology. This year, we hauled up our computers, printers and a massive digital duplicator, determined to become Black Rock City's third daily newspaper. Even Spock was surprised by our success - news will never be viewed the same on the playa. Read all seven issues of the 2002 Spock Science Monitor for yourself and see why. (More...)

Skunk School -- Learn Why Not To Keep Skunks As Pets

There is an alarming trend in pet purchasing habits this fall. People inspired by the WWII film, "Life is Beautiful" -- the one with that annoying Italian guy -- are buying descented skunks by the millions. (More...)

Patient Joab's scientifick editorial discusses aspect of the space-time-beer continuum never before processed by sub-bush-robot minds!!! Too fabulantastic to contempulate! (More...)